On March 3, 1969 the United States Navy established an elite school for the top one percent of its pilots. Its purpose was to teach the lost art of aerial combat and ensure that the handful of men who graduated were the best fighter pilots in the world.

They succeeded.

Today the Navy calls it Fighter Weapons School.

The flyers call it: “TOP GUN”

Hollywood action film aficionados will recognize this as the introduction to the Top Gun movie franchise starring Tom Cruise. Not long after the release of the latest installment, the editor of PelhamToday (at that time the Voice) asked if I might comment on the authenticity of the films. I assume he did this because of my 20 years of experience as a fighter pilot in the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), the bulk of that time spent on the F-18 Hornet—the fighter featured in Top Gun: Maverick.

My initial response was no, it’s a movie not a documentary, with the comparison of fact vs. fiction heavily lopsided to the fictional fluff required to keep an audience with an average attention span of two nanoseconds riveted to the screen for 90 minutes. Not easily deterred, the editor appealed to a fighter pilot’s one weakness and offered to buy me a beer if I would give it a shot. Obviously, I had no choice. Since the list of fictional aspects of Top Gun would require me to spend the rest of my retirement typing furiously with two fingers, I’m limiting this discussion to “just the facts.”

The cinematography in Maverick is brilliant and as close to actually being in a Hornet as I’ve ever seen. The producers (read Cruise) wanted to reproduce the sights and sounds of naval fighter aviation while minimizing the use of computer-generated imagery. The United States Navy (USN) provided F-18E (single-seat) and F-18F (two-seat) Boeing Super Hornets for the movie, and even painted two aircraft with light and dark blue stripes along with Capt. Pete “Maverick” Mitchell stencilled on the canopy rails. The Navy also allowed Cruise and some of the cast members to fly in the backseat of the F-18F. For this privilege, the producers were charged $11,374 per flight hour. This was a win-win situation for Cruise and the Navy. It provided Cruise the reality he was looking for and the Navy an opportunity for the same spike in recruitment that took place after the original Top Gun was released in 1986.

First off, let’s be perfectly clear that no actor was ever flying in the front seat, and while they were in the backseat they were forbidden from touching the flight controls. The aircraft were loaded with a multitude of cameras, most of which were in the backseat. To Cruise’s credit he insisted that all actors complete an indoctrination program of aerobatics in a series of small propeller and jet trainers to build a tolerance to the maneuvers and the high-G environment they would experience in the Hornet. This was an attempt to keep the actors conscious, prevent them from vomiting all over the cockpit, and perhaps sort of look like they knew what they were doing.

To maximize flight safety, all pilots provided by the Navy were experts in the type of flying being filmed. For example, the ultra-low-level high-speed scenes were performed by an experienced Blue Angel (Navy Air Demonstration Team) pilot who was able to safely operate at altitudes of 30 feet above the ground. Air Combat Maneuvering (ACM) segments were flown by actual Top Gun instructors who specialized in dogfighting.

Spoiler alert: The Dark Star hypersonic aircraft was only a mockup provided by Lockheed-Martin’s Skunk Works research and development arm, and was not airworthy (no engines—a big problem). It was their attempt to depict what a hypersonic aircraft might look like, and any flying scenes were all computer generated. Sorry, no Mach 10 (ten times the speed of sound) for Maverick—that’s only in the metaverse.

The preamble to both movies is factual. The First World War saw the birth of aerial combat with machine guns being strapped to early model aircraft, and soon dogfights erupted over the skies of France. (As an aside, the emergency radio distress call “MAYDAY” originated around this time, derived from the French m’aidez—“help me.”)

The machine gun and larger-calibre cannon were the only weapons used in air-to-air combat for the next 40 years. It wasn’t until the 1950s and the jet age that missiles (both radar-guided and heat-seeking) were developed.

Rather than having to maneuver the aircraft to a position 1500 ft. or closer behind the enemy (gun range), a pilot could now launch a missile from miles away at almost any angle. Military planners and aircraft manufacturers were so confident in this new technology that they started removing machine guns from fighters. This resulted in changes to tactics and training with little emphasis on air combat maneuvering. It wasn’t until the Vietnam War that it became obvious the lethality of missiles wasn’t quite as advertised and the Navy (and Air Force) were experiencing an unacceptable loss rate. Hence the need to teach the lost art of aerial combat and establish a fighter weapons school.

The origins of all fighter weapons courses started with the United States Air Force (USAF) at Nellis Air Force base near Las Vegas, Nevada, in the late ‘50s. The course was four months long and consisted of flying air-to-air and air-to-ground missions in conjunction with extensive ground school. Graduates returned to their squadrons and were responsible for ground school instruction, airborne training and evaluation.

In 1972 the RCAF sent Colonel Phil Engstat to Nellis for a two-year tour of duty flying the F-4 Phantom at the USAF Fighter Weapons School. Not only did Phil have to learn to fly the F-4 (Canada didn’t own any), but he also completed the Fighter Weapons Course and then became an instructor on the course, making this an unbelievable accomplishment.

Phil returned to Canadian Forces Base Cold Lake Alberta in 1974 and became the “godfather” of the RCAF Fighter Weapons Course, passing on the wealth of knowledge and experience he accumulated during his time in the States. The Canadian Fighter Weapons School continues to this day in Cold Lake thanks to the efforts of Phil and a cadre of excellent pilots.

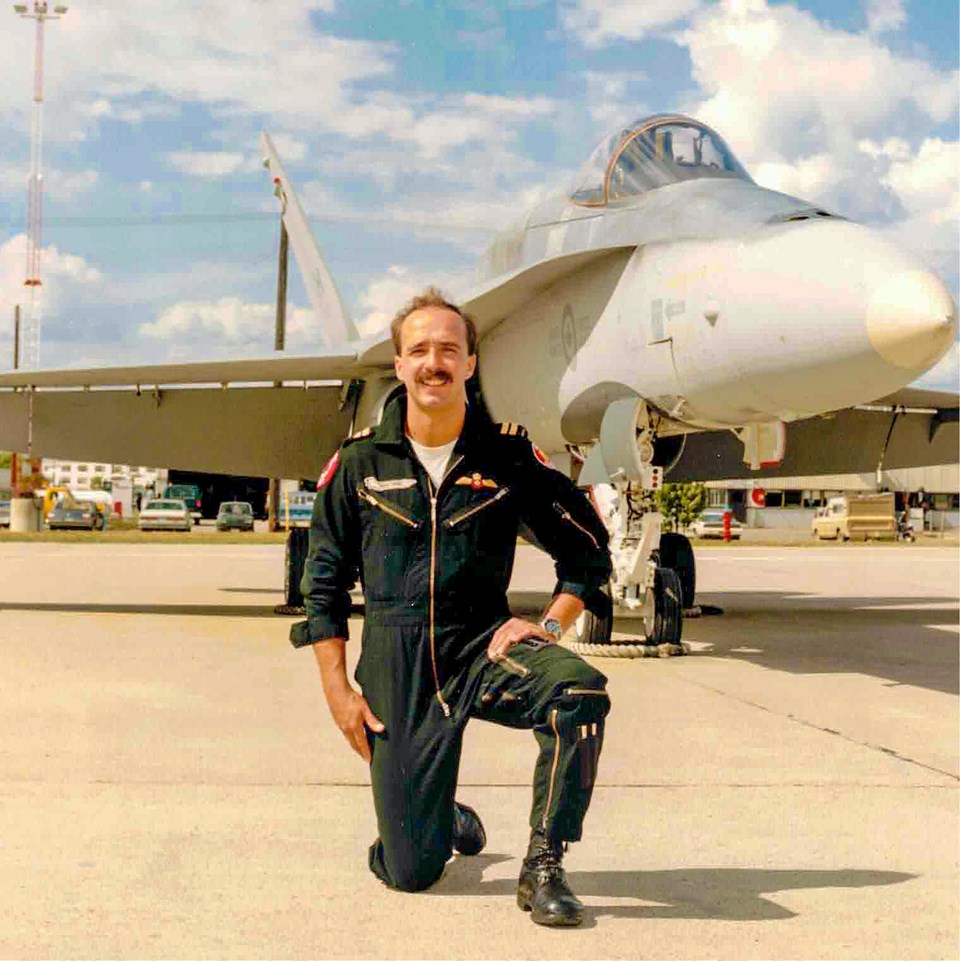

In the movies, Cruise portrays Top Gun pilots as ruggedly handsome, incredibly intelligent, loyal, trustworthy, competitive, and above all modest to a fault. In the interest of full disclosure, I’m a graduate of the RCAF Fighter Weapons Course and was an instructor at the school, so perhaps I embellished that last bit ever so slightly.

Top Gun: Maverick was a very entertaining and successful movie, earning US $1.5 billion and attracting six Oscar nominations. It’s too early to determine how much influence it will have on military recruitment, but it couldn’t have come at a better time for Canada. After years of neglect, the Canadian government finally announced it will be purchasing 88 Lockheed Martin F-35s to replace the F-18s we have been operating for the past 40 years. For keen-eyed observers, the F-35 made some cameo appearances in the opening scenes of Maverick on the aircraft carrier flight deck.

Young Canadians who, after watching the movie feel the need for speed and think the idea of being the best of the best in aviation is appealing, have the opportunity of a lifetime for the taking. I only wish I were 50 years younger so I could march down to the recruiting centre and do it all again.

Per ardua ad astra

VIDEO | Flight operations aboard the USS Harry S. Truman (CVN-75) include multiple takeoffs and landings of F/A-18 Hornets and one takeoff of an E-2 Hawkeye. Credit: Seaman Apprentice Ethan Schumacher.