This article, written by David Webster, Bishop's University and Greg Donaghy, University of Toronto, originally appeared on The Conversation and has been republished here with permission:

Conservative Leader Andrew Scheer is promising to cut overseas aid by 25 per cent.

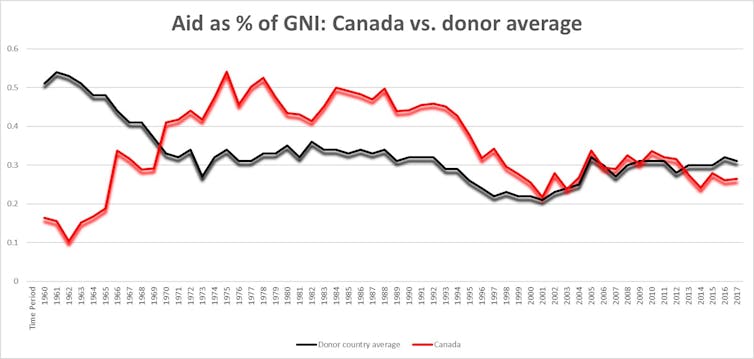

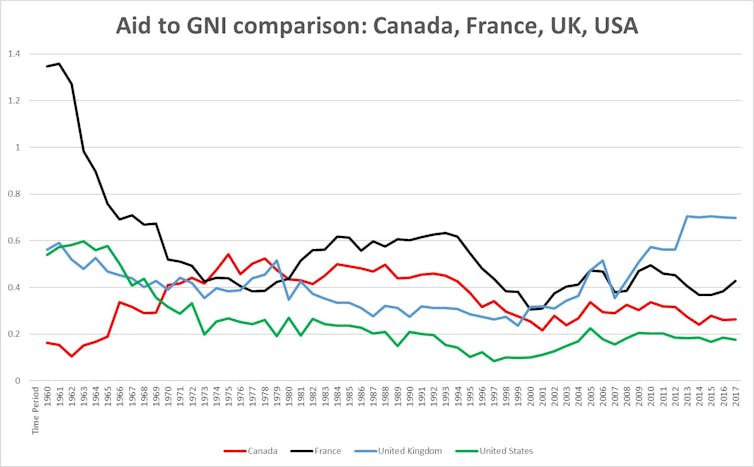

Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau pledges to increase aid, but will still leave the amount Canada spends on aid at barely 0.28 per cent of Canada’s gross national income, well below the levels attained by previous governments.

Neither one shows much awareness of the twists and turns of Canada’s 70 years in the aid field, or a willingness to learn from the past. Both seem to assume aid is an act of pure generosity.

Yet as the contributors to our new book, A Samaritan State Revisited, demonstrate, government policy goals have been much more important than altruism in shaping Canadian aid.

Compared to the size of our economy, our aid has been slipping since the 1980s, and Canada lags behind most other donors. Time and again, we have failed to match our rhetoric with action. We’ve been a middle-of-the-pack aid donor rather than the global leader we should be.

The first Canadian ventures into aid built on relief efforts in Europe during and after the Second World War, especially the massive mission by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA). Canada sent aid both multilaterally, through the UN and its agencies, as well as bilaterally to favoured countries. It pledged both technical assistance (experts, scholarships and skills transfer) and capital aid (money for major development projects).

Branding projects

Within the Colombo Plan, the Commonwealth’s aid scheme for Asia that Canada helped launch in 1951, recipient governments drew up their own development plans and donors pitched in, sometimes in exchange for the chance to “brand” projects — a Canada dam here, a Canada bridge there.

Aid was linked to Canadian products, serving as economic stimulus at home. If India needed tractors or Burma needed rail cars, and no Canadian company made them, then Canada wouldn’t provide them as aid.

Still, Canada manufactured plenty of things, and was willing to send them to Asia — at least to those parts that were non-communist and, most especially, Commonwealth members.

In the first 15 years of Canada’s aid program, from 1950 to 1965, 95 per cent of Canadian assistance flowed to three Asian Commonwealth member countries: India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. Aid administration and project selection was freewheeling and creative, open to recipient government priorities.

Ottawa left the big picture to the UN, its aid programs distinct but conceived as part of a bigger multilateral effort —not a bad summary of how Canadians saw their foreign relations as a whole.

Africa, the Caribbean

By the late 1950s, requests from newly independent states in the Caribbean and Africa prompted the creation of more programs. And domestic pressure to respond to demands from French Canada for a foreign policy reflecting Canadian biculturalism spawned cultural, educational and economic aid packages for francophone West Africa, the Caribbean and Latin America.

In 1960, Progressive Conservative prime minister John Diefenbaker moved all aid operations to a new External Aid Office (EAO). Almost overnight, aid scattered in an ad hoc fashion over poorer parts of the globe became “development assistance.”

It was a structured and often multilateral approach that marshalled technical and capital assistance, trade and financial policy and co-ordinated donor support into a complex and long-term campaign for social change and economic growth.

In May 1968, egged on by its reformist director-general, Maurice Strong, Liberal prime minister Pierre Trudeau transformed the EAO into the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA). In doing so, Trudeau’s government signalled its intention to become a major player in global aid, an ambition marked by a growing roster of recipient countries and a rising aid budget.

The evolving shape of Canadian aid administration echoed global trends, epitomized in the work of a UN-backed Commission on International Development chaired by former Liberal prime minister Lester B. Pearson. The result was Partners in Development, a report released in 1970 that famously set 0.7 per cent of gross national income as the amount that wealthier states ought to spend on development assistance.

Under Strong and his successor, Paul Gérin-Lajoie, CIDA became almost a state within a state. The agency offered room for thinking about development differently. Yet results fell short of the rhetoric.

Measured as a percentage of GDP, Canadian aid under Trudeau reached its pinnacle at 0.54 per cent in 1978 even as other government departments tied CIDA’s budget to broader foreign policy goals. Commercial considerations, in particular, came to the fore.

Canada’s aid-to-GDP ratio briefly recovered to 0.5 per cent in 1988 under Progressive Conservative prime minister Brian Mulroney. His government backed CIDA president Margaret Catley-Carlson’s stress on boosting civil society, helping the poorest and promoting “women in development.”

Yet public support for aid was flagging. In a 1985 Decima survey, half of respondents thought that aid was at the right level, whereas only 24 per cent wanted it to increase and 17 per cent judged it too high.

Cuts to aid begin

So there was not much political cost for governments that wanted to reduce Canada’s involvement in international development. Cuts began under Mulroney in 1989 to 1992, reflecting both a desire to trim deficits and the decreasing prominence of aid as the Cold War sputtered to an end and the Global South ceased to be an arena of superpower contestation.

Global trends after the Cold War made aid increasingly conditional on the neoliberal structural adjustment programs championed by international financial institutions like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund and major donor states.

Under its president, Marcel Massé, CIDA embraced this free market “Washington consensus,” pushing governments in the Global South to deregulate their economies, reduce public spending and turn to market-based policies.

In a reflection of Canadian trade goals, CIDA prioritized more middle-income countries such as Indonesia and China as major recipients, while cutting out lower-income countries.

Mulroney also began to dismantle the architecture of public engagement on which CIDA’s popular support had rested. The process accelerated under Liberal prime minister Jean Chrétien and culminated in the outright hostility toward many aid NGOs expressed by Conservative prime minister Stephen Harper’s government.

Hapless CIDA officials were unable to defend their agency from calls to merge it with the much larger Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, a merger accomplished in 2013.

Canadian aid has moved through new policies and new priorities over the decades, but coherence has long been lacking.

Its current rate of 0.28 per cent of gross national income is half of its 1970s peak and well below the average for all donor states. Ambitious positioning of Canada as global leader is undermined by the scant resources allocated to aid.

Still, Canadians see their country as generous and sympathetic, and Canadian governments have never ceased to be major players in global development debates. A Samaritan State Revisited reminds us that Canada is neither a heroic do-gooder nor an imperialist exploiter. Rather, our country is in a more ambiguous position that has both reflected and shaped global trends in Canadian development thought and practice.

The erosion of public support for aid under Mulroney, Chretien and Harper made Canada’s meagre aid a tempting target for cuts — even as the facts show that Canada is a laggard, not a leader, on aid.

[ You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter. ]![]()

David Webster, Associate Professor of History / Professeur Agrégé, Département d’Histoire, Bishop's University and Greg Donaghy, Director, Bill Graham Centre for Contemporary International History, University of Toronto

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.