This article, written by Peter Jaskiewicz, L’Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa; Alfredo De Massis, Free University of Bozen-Bolzano, and Marleen Dieleman, National University of Singapore, originally appeared on The Conversation and has been republished here with permission:

Born between 1981 and 1996, millennials differ more from their parents than the last two generations, exhibiting a greater sense of purpose, willingness to move abroad and eagerness to explore new opportunities.

This leaves aging parents who own family businesses wondering about the future of their companies. Family businesses, among the most common forms of organizations around the world, are firms owned or managed by one or more founding family members. Passing the business onto the millennial generation, however, appears to be more difficult than it was previously.

Despite being more educated, technologically adept and global in vision, only 4.9 per cent of millennials intend to take over their respective family businesses, according to 2017 research.

Does the older generation need to urgently adapt, or should they leave the family business to outsiders? It depends. Millennial participation may actively rejuvenate some businesses, improving the agility of the company in the face of economic, digital and sociopolitical change.

However, millennials with different ideas about how to run the business may also create unhelpful turbulence in the family and its company, suggesting they might be better off using their talents elsewhere. We therefore asked: Which types of transitions exist, and which one should families choose?

Our decade-long research program analyzed more than 400 interviews and conversations with members of family businesses around the globe.

Millennial succession

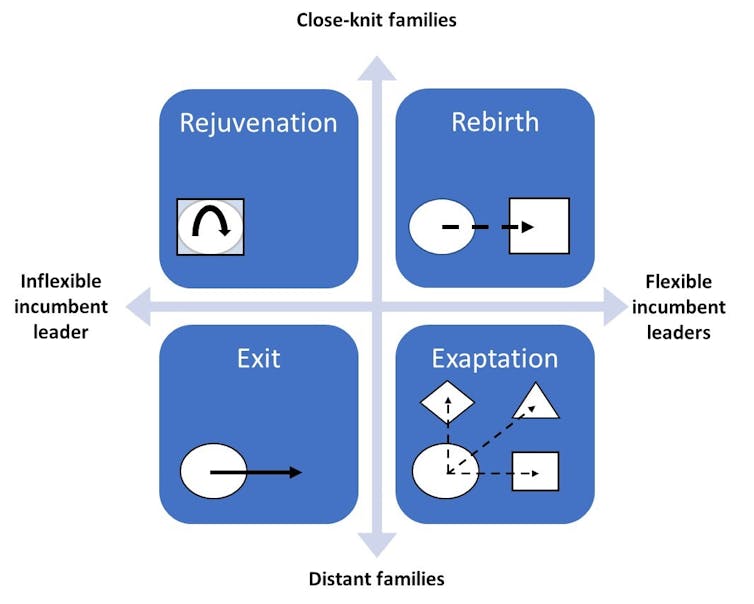

We discovered two dimensions that mattered for millennial succession:

-

Families that are more close-knit lean towards intergenerational collaboration, whereas more distant ones push generations apart.

-

The flexibility of incumbent leaders in family firms influences the freedom that millennials have in the family business. Less flexible leaders insist on maintaining traditional family practices. Others are more open to changing the course set by previous generations.

Based on these dimensions, our study identified four transition strategies, illustrated below and based on previous published research — rejuvenation, rebirth, exit and exaptation:

Rejuvenation: Embracing the family legacy

Families that succeed with a rejuvenation strategy tend to be close-knit across generations and inclined to follow the family tradition. Trust between generations encourages co-operation, and younger family members go along with the family’s way of doing things, knowing that they are responsible for the future of the family firm.

This transition is often the smoothest, supported by effective family governance, leveraging the strengths of multiple generations. Millennials are encouraged to stay close to the incumbent generation — even if this means giving up on personal aspirations.

Incumbent family members may also support millennials in their pursuit of entrepreneurial projects when acceptable to the retiring generation. This transition strategy serves as a benchmark for most incumbent business owners.

Rebirth: Turning over a new leaf

Some close-knit families feature both incumbent and younger family members openly collaborating on major business decisions, displaying high levels of flexibility.

Millennials in these families are generally inclined towards joining their parents in the family business. Incumbent family members are more open to their offspring’s ideas both inside and outside the business, emphasizing that they do not want to burden their children with running the family business.

Despite their openness to contemporary ideas, the closeness of the family may still cause it to favour tradition. However, support from incumbent family members empowers millennials to enact more radical change — which can include the transformation of the family business in terms of business model.

The choice to move away from older business models towards new goals may in fact be for the best, even if these new goals may only be marginally linked to the original business.

Exit: The world is an oyster

This strategy is often seen in families with low intergenerational cohesion and lacking flexible leaders. Incumbent leaders have often endured self-sacrifice for the family and business, and typically prioritize business over family. Millennials are detached from the business and may not identify closely with it or other family members.

They have many opportunities to leave and few reasons to return — in fact, many seek to study or work far from home.

Placing business needs above all else may place a psychological burden on the next generation, fuelling their desire to leave family and business behind. This, in turn, leaves older generation members scrambling to figure out a succession plan and pushes them to cling on to familiar traditions.

This behaviour pattern can lead to even greater rifts in an already distant family, sometimes exacerbated by poor company performance. However, these businesses may be able to survive with very little family involvement by finding capable outsiders to take on business roles.

One example of exit is Italy’s Merloni family, which sold its controlling stake in the family business — Indesit, the largest producer of household appliances in the country — to Whirlpool for 758 million euros amid rumours of disagreements in the family over strategy.

Exaptation: Out with old, in with new

Families with low unity but flexible leaders often see their children follow their own dreams. Greater parental flexibility reduces the pressure on millennials to inherit the family firm.

Motivated by a need to step back and retire, family incumbent leaders see the business as a tool to support both themselves and the next generation. This support may result in the younger generation pursuing new entrepreneurial activities only loosely linked to, or even separate from, the original business. The older generation is perfectly fine with this behaviour and adopts a “hands-off” approach.

This is often portrayed in the media as the end of longstanding family business dynasties. However, the younger generation may build a different yet equally powerful legacy. The distance between generations allows millennials to pursue projects on their own terms, yet often with parents’ support, transforming the family legacy into something new.

All families differ

Every family is different — some are close, others are distant, still others are dysfunctional. Additionally, family business leaders also differ — some are flexible, others are more rigid.

Passing on the traditional family firm to a millennial, which we call the rejuvenation strategy, is not necessarily the best one. We argue that imposing a transition that is misaligned with family and leader characteristics is more likely to fuel conflict and, ultimately, fail.

Alternative options such as rebirth or exit may not always keep the old business in the family, but may be a wiser choice and could contribute more positively to the family’s legacy and society at large.![]()

Peter Jaskiewicz, Professor and University Research Chair in Enduring Entrepreneurship, L’Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa; Alfredo De Massis, Professor in Entrepreneurship and Family Business, Free University of Bozen-Bolzano, and Marleen Dieleman, Associate Professor, Strategy and Governance, National University of Singapore

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.